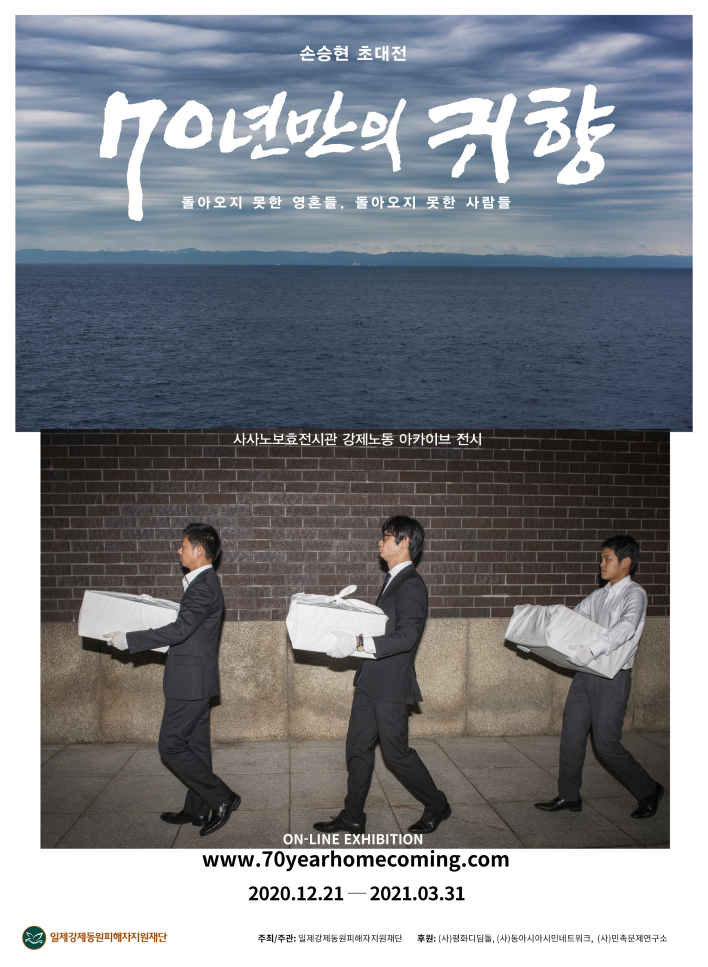

손승현 온라인 초대전

70년 만의 귀향:

돌아오지 못한 영혼들,

돌아오지 못한 사람들

Sohn Sung Hyun

On-line Exhibition

70YEAR HOMECOMING:

DISPLACED SOULS, DISPLACED PEOPLE

작가 소개

About Artist

손승현

Sohn, Sung Hyun

孫昇賢(ソン·スンヒョン)

사람과 그 주변에 대한 관심으로 사진작업을 진행하고 있다. 한국인을 비롯한 몽골리안의 역사, 사회, 경제에 관한 이야기를 시각예술작업으로 진행하고 있으며 북미 원주민 공동체에 깊숙이 들어가 이들의 과거와 현재에 대한 여정을 함께하고 있다. 해마다 몽골과 북미 여러 곳을 여행하며 주된 작업인 사진작업과 글쓰기를 통하여 기록한 내용을 바탕으로 폭넓은 이야기와 현실 문제에 대한 문명비판도 병행하고 있다. 2002 광주 비엔날레를 비롯해 뉴욕, 이탈리아, 독일, 일본, 중국, 호주,몽골 등지에서 80여 차례 전시에 참여했고 국내외의 여러 출판 프로젝트를 진행했다. 지은 책으로 미국 원주민의 이야기인 『원은 부서지지 않는다 (The Circle Never Ends)』(아지북스, 2007)와 『제 4 세계와의 조우 (Close Encounters of the Fourth World)』(지오북, 2012), 사진집으로『밝은 그늘 (Bright Shadow)』(사월의 눈, 2013), 삶의 역사- 안산, 홋카이도, 사할린, 그리고 타슈겐트 (한양대학교 글로벌 다문화연구원, 2015) 그리고 공역서로 원주민 구전문학인 『빛을 보다 (Coming to Light)』(문학과지성사, 2012)가 있다. 한국 시각인류학회 연구위원으로 활동하고 있으며 뉴욕을 기반으로 하는 초상사진가 그룹 누토피아 포럼(Nutopia Forum)의 멤버이다. 현재 한국인의 근대와 이산문제, 제 4세계 사람들(선주민)에 대한 광범위한 사진작업을 진행하고 있다.

전시 소개

About Exhibition

70년만의 귀향:

돌아오지 못한 영혼들,

돌아오지 못한 사람들

70Year Homecoming:

Displaced Souls,

Displaced People

광복 75주년을 맞아 사진전 〈70년만의 귀향: 돌아오지 못한 영혼들, 돌아오지 못한 사람들〉을 기획했습니다. 홋카이도

강제노동 희생자 유골 발굴은 1980년대 일본의 시민과 종교인으로부터 시작되었습니다. 그리고 1997년부터 22년간

한국과 일본, 재일동포, 아이누 청년들이 함께 태평양 전쟁 시기 강제노동으로 희생된 50여구를 발굴하고, 인근 지역

사찰 등에서 100여구의 유골을 수습했습니다.

지난 2015년에는 이 유골들 중 115구를 한국으로 모셔왔습니다. 정부차원이 아닌 순수한 한, 일 시민들의 힘으로 유골을

가져오게 되었습니다. 그리고 2011년부터 약 십년 동안 기록된 사진을 통해 유골을 둘러싼 유족 및, 한일 시민들의

관계를 묻는 전시를 기획하게 되었습니다. 유골 이야기의 시작은 홋카이도 슈마리나이 호수 근처에 위치한 구

광현사(사사노보효: 조릿대 전시관)강제노동 전시장에서 시작됩니다. 1970년대 중반, 도노히라 스님의 우연한 광현사

방문에서 유골발굴의 모든 일의 시작되었습니다.

태평양 전쟁 이후, 일본 홋카이도에 강제 연행당한 한국 사람들의 유골이 있다는 사실은 알려져 있었지만 방치된 채로

60년 이상 흘러가 버렸습니다. 강제 연행과 강제 노동은 일본 정부가 전쟁 정책을 펴는 과정에서 일어난 일이고

관련기업들이 많은 사람들을 그들의 고향으로부터 끌고 와서 죽음으로 내 몰은 것이라 할 수 있습니다.

강제연행, 강제노동 인류 보편의 문제입니다. 인류에 대한 죄악입니다. 일본 정부와 기업이 책임지지 않고 지나간 일을

한국과 일본의 시민들이 알게 되고 인간을 존중하는 가장 기본적인 일로써 희생자 유골을 발굴해 그들의 고향으로

돌려보내 주는 일을 시작하게 됩니다.

희생자 유골 발굴은 가해자나 피해자의 입장에서만 접근해서는 결코 해결될 수 없는 일이며 유골 발굴과 관련된 모든

사람들이 함께할때 비로소 단절된 인간관계가 회복되고 새로운 인간관계의 형성이 가능해집니다. 강제노동 희생자 유골

발굴을 위한 한,일 공동 워크숍은 이러한 일들이 가능했음을 보여주는 사례입니다. 이것은 목숨을 잃은 유골이 살아있는

사람들을 다시 연결하는 일을 하는 것입니다. 〈70년만의 귀향: 돌아오지 못한 영혼들, 돌아오지 못한 사람들〉

사진전을 통해 한.일, 재일동포, 아이누 시민들이 국가 간 갈등을 넘어 어떻게 교류하고 서로 이해하고 힘을 합쳐

유골발굴을 통한 만남을 지속하고 있는지를 살펴보시기를 바랍니다.

아울러 현재 교착된 동아시아의 평화에 관해서도 다시 생각해보는 계기가 되시길 바랍니다.

손승현 온라인 초대전

70년만의 귀향:

돌아오지 못한 영혼들,

돌아오지 못한 사람들

- 기간

- 2020.12.21.(월) –

2021.03.31.(수)

- 전시총괄

- 손승현

- 주최/주관

- 일제강제동원피해자지원재단

- 후원

- (사)평화디딤돌, (사)동아시아시민네트워크, (사)민족문제연구소

- 전시행정

- 이정은

- 전시운용

- AGI Society

- 온라인 전시 기획/개발

- Rebel9

- 포스터 디자인

- 김영철

- 사사노보효전시관 기획/아카이브 감수

- 박진숙, 양월운

- 도움주신 분

- 김영환, 김현태, 박수진 박사, 송기찬 박사

- 사진, 글, 비디오

- 손승현

- 사운드 설치

- '재는 눈으로'(02:29) 써니킴(목소리), 심운정(타악기). 이선재(녹음), 사운드 디자인: 써니킴

- 사진 비평글

- 이영준 박사, 박평종 박사

- 번역

- 최춘호(일본어), 고아람(영어), 도노히라 유코(영어)

- 필름 스캔 및 디지털이미지 보정

- 칼라랩

- 갤러리 전시 및 연계 프로그램

- 2021년 2월 중 예정(엘리펀트스페이스, 서울)

☞ 사용자의 PC, 브라우저 환경에 따라 관람 환경에 제한이 있을 수 있습니다. 사이트는 Chrome, Firefox, Safari의 최신 브라우저 이용을 권장합니다.

☞ Copyright 2020, 손승현 작가의 서면 동의없이 이 웹사이트에 실린 사진 및 글, 비디오의 일부 또는 전부를 무단 전재,복제, 발췌할수 없습니다.

Homecoming

손승현(전시총괄)

사람이 세상에 와서 살아갈때 사회 공간 속의 많은 제도,환경과 관계 맺으며 살아간다 나는 그 동안 한반도에서 태어나

한국을 떠났거나 오랜 시간 지나 다시 고향으로 돌아온 사람들, 고향으로 돌아간 사람들, 그리고 돌아오지 못한

사람들의 이야기를 사진으로 기록했다. 나의 궁극적 관심사는 사람들이 살아가는 사회적 모습들과 사람들에게 그런

사회적 삶을 살게 하는 사회적 환경, 제도들이다. 한국인들이 각기 고향을 떠나 살아가야 했던 낯선 이방인의 땅, 각기

다른 사회 속 제도와 관습, 권력 등은 사람의 모습과 얼굴모양 마저도 바꾼다. 이번 전시에서 보여지는 사진들은

지난100년 동안 미국을 포함해서 일본, 중국, 러시아, 사할린, 중앙아시아 등 세계곳곳을 떠돌아 다니면서 살아야만

했던 기구한 운명의 한국 사람들의 역사적 증언으로서의 인물기록사진이다. 현실의 삶이 척박하고 힘들고 괴로워도

아름다움과 결합될 때 긍정적 효과와 연결된다는 생각을 사진작업을 통해 드러내고자 했다.

이번 온라인 사진전은 유럽, 아메리카, 러시아 사할린 동포, 중앙아시아 고려인 동포들, 조선족 동포, 북한 이탈

주민들(새터민), 재일동포들을 비롯한 코리안 디아스포라의 초상이 전시된다 또한 북으로 송환된 비전향 장기수,

한국사회에서 합법적인 국민으로 살아왔지만 냉전과 분단이라는 한국사회의 암울한 역사 속에서 어쩔 수 없이 우리

사회의 소수자로 인식되어온 사람들을 만나고 그들의 이야기가 사진으로 전시된다. 전시는 한국에서 이주한 다른

사회에서 겪어야 했던 한국 이주민의 이야기를 통해 오늘날 다양한 문화계층이 공존해 살아가는 한국의 사회적 상황을

이해하는데 목적이 있다. 전시는 한반도를 둘러싼 정치, 역사적 사건으로 인해 오랜 기간 타국에서 다른 문화 속에서

살아온 코리안 디아스포라 인들의 이야기와 초상을 기록한다. 이번 전시는 지난 20여년간 기록한 “70년만의 귀향”,

“사사노보효전시관 강제노동 아카이브 전시”, “돌아오지 못한 영혼들”, “돌아오지 못한 사람들” 등 4개의 사진작업이

전시된다.

지난 20여년간 조국을 떠나 타국의 삶의 경계에서 아슬아슬하게 살아온 수많은 한국인들을 만나고 그들의 이야기를

들었다. 그들 수백명 한명 한명의 이야기가 가슴속 깊이 새겨졌다. 작가로써 가졌던 질문들 인간이란 과연 무었일까?

인간은 무엇으로 살아갈까? 에 대한 나의 기대를 몇 십배 넘어가는 놀라운 삶의 이야기 때문에 이야기를 들으며 많이

울었고 그 삶들로부터 여러가지 배울수 있었다. 이제는 작고 외소해진 사람들의 살아온 과거 이야기를 듣고나면 그들에

대한 경외심이 생겼다. 그리고 그들의 삶을 이야기를 듣고 난 뒤에는 그 삶들에 대한 존경으로 진심으로 안아드리고

위로드리고 싶은 사람들로 보였다. 내 가슴속에서 반응한 것은 이 사람들의 놀라운 ‘생명력’ 이었다. 감당하기 불가능한

힘들고 어려운 선택이 인생의 매 순간 다가와도 회피하지 않고 정면으로 맞선 사람들의 얼굴은 삶의 지도와 같았다.

사진을 통해 이 사람들의 보이는, 그리고 보이지 않는 부분의 삶의 모습을 이야기 하고자 사진작업을 해왔다.

“억눌린 자들의 전통이 우리들에게 가르치고 있는 교훈은, 우리들이 오늘날 그 속에서 살고있는 “비상사태 the state of

Emergency” 라는 것이 예외가 아니라 항상 같이 한다는 것이다.”

— 발터 벤야민, “역사철학테제”

70년만의 귀향

70Year Homecoming

손승현

Sohn, Sung Hyun

제2차 세계대전당시 일본식민하에 있던 한반도에서는 수십만의 젊은이들이 전쟁을 수행하기 위해 탄광, 기지건설,

군인으로 강제로 끌려가야만 했다. 전후 일본정부는 전쟁 때 희생된 수많은 강제 징용 희생자들을 아무렇게나 방치한 채

일본 곳곳에 버려두었다. 그들은 한일정부의 무관심 속에 잊혀져 갔다. 희생된 사람들을 기억하고 그들의 유골을 그들의

고향으로 되돌려 주려한 일본시민, 종교인에 의해 어둠 속에 잊혀진 희생자는 다시 빛을 보게 되게 되었고 한 많은

유족들을 찾아 유골을 돌려주고 위로해 주는 일이 시작되었다.

태평양전쟁 이후, 연합군 포로나 중국의 징용자 유골은 오래 전 그들의 조국으로 돌아갔지만 식민지 조선 출신의

희생자들은 죽어서도 차별 받았다. 심지어 군인으로 징병된 희생자들은 유족에게도 알리지 않고 일본의 야스쿠니 신사로

합사시켜 버렸다. 홋카이도는 14만 5000명의 조선인 징용기록이 있고 확인된 희생자만 수 천명에 이른다. 홋카이도의

강제노동 희생자 발굴은 1976년 도노히라 스님(전 일승사 주지스님)의 우연한 슈마리나이 폐사찰 (광현사, 현

사사노보효전시관) 방문으로 시작된다. 그리고 스님이 만나게 된 80여개의 우류댐 희생자 묘표로부터 홋카이도 강제징용

희생자 발굴 작업은 조사, 시작되었다. 1970, 1980년대 지역단체인 '소라치 민중사 강좌’ 회원들을 중심으로 유골발굴을

진행했고 많은 유골을 발굴해 한국으로 유족과 연락하고 희생자들을 고향으로 돌려보내기 시작했다. 이후 1997년 한,일

공동 워크숍으로 더 많은 양국 시민 학생들이 만나면서 희생자 발굴작업은 더 큰 규모로 이루어졌고 지난 20여년간

공동작업이 되었다. 서로를 이해하고 소통하고 역사의 진실을 만나는 교류의 장이 된 것이다.

"70년만의귀향작업" 은 홋카이도에서 그간 발굴된 유골과 인근 사찰에 보관중인 유골 115구를 희생된 징용자들이 끌려간

그 길을 되돌아오는 여정으로 송기찬 교수에 의해 기획되었다. 한국에서 출발해 돌아오기까지 3,800킬로미터 열흘간의

여정은 2015년 광복 70주년이 되는 해에 실행되었다. 비행기로는 세관, 검사 통관 등 여러 문제들이 발생했기에 버스와

배를 통한 여정으로 구체화되었다.

여정의 시작은 홋카이도 북쪽 끝자락에 위치한 아사지노 일본 육군 비행장 강제노동 희생자 34구의 유골을 임시로

안치해 둔 북쪽 마을 절에서 추도식이었다. 이곳에서 슈마리나이 광현사를 들러 4구의 유골을 모시고 비바이시의

미쯔비시 탄광에서 희생된 6구의 유골(조선인 5000명의 징용자 기록)과 정토진종 삿포로 별원에서 합골된 유골중 남한

출신 희생자 유골 71구를 분골해 모시고 여정을 떠났다. 삿포로 남단 토마코마이 항구에서 도쿄인근의 오오아라이

항구를 출항했다. 징용자들이 끌려간 바닷길을 따라갔다. 당시, 징용자들은 두 번의 바다를 건너며 절망 했다고 한다.

도쿄와 교토, 오사카, 히로시마, 시모노세끼를 들리면서 희생자들이 그들의 고국으로 돌아감을 알리고 과거의 진실과

마주할 기회를 만들게 된 것이다.

귀향단은 시모노세키에서 무사히 대한 해협을 건너 부산 항에 도착했고 노제를 올리고 장례식이 거행될 서울 시청

광장으로 이동했다. 많은 자원봉사자와 유족들 그리고 시민들이 참여한 장례식을 치른 뒤 유골은 화장을 거쳐 파주

시립묘역에 안장 되었다. 아직도 일본 전역에는 수만의 방치된 강제 징용 희생자 유골이 방치되어 있다. 더 늦기 전 에

서둘러 옮겨와야 한다. 양국 정부가 못한다면 "70년만의 귀향"처럼 양국 시민의 힘으로 진행하면 된다. 유골을 그들의

고향으로 돌려주는 일은 인간으로써 가져야 할 가장 중요한 일이다. 한국과 일본의 양심적인 종교인, 활동가 분들께

다시 한번 감사의 인사를 올린다.

70년만의 귀향

손승현

〈70년 만의 귀향〉은 강제 징용된 희생자를 고국으로 돌려 보내는 여정을 기록했다.

제2차 세계대전 당시 일제 강점기의 한반도에서는 수많은 젊은이들이 전쟁터로 끌려갔다. 전쟁 노역으로 강제 징용된

이들은 일본 본토 내 탄광에서 강제 노역을 하거나, 군속으로 차출되어 동남아 지역의 기지 건설에 동원되었다. 특히

지하자원이 풍부한 일본 최북단의 섬 홋카이도 지역으로 14만 명의 조선인이 끌려갔다. 겨울이 유난히 길고 추워

강제징용 자들이 가장 기피한 곳이라 알려진 홋카이도에서만 수 천명의 조선인이 강제 노동으로 희생됐다.

일제는 패망했지만 일본 정부는 수많은 강제 징용 희생자 유해를 일본 곳곳에 그대로 내버려두었다. 심지어 일본 정부에

보고된 절반 이상의 유골은 다른 사람들의 유골과 뒤섞여 개별성조차 잃어버렸다. 한 예로 삿포로 별원은 한국인,

중국인, 일본인 등의 강제 징용 희생자 101명의 유골이 뒤섞인 3개의 항아리를 보관하고 있었다. 그러나 일본 정부의

무책임한 태도와 달리 삿포로 별원에서 찾은 희생자의 존재와 신원에 대한 단서는 일본 시민들과 종교인의 관심으로

발견할 수 있었다. 희생자를 기억하고 이를 안팎으로 알렸던 일본 시민들과 종교인들은 얼마후 한국 시민사회와 함께

활동하며 한 많은 유족을 찾아 유골을 돌려주는 일을 시작했다.

1976년 슈마리나이 폐사찰(현 사사보노효 전시관)을 방문한 도노히라 요시히코 주지 승려는 우연히 조선인 이름의 위패

수십개를 발견했다. 이에 의문을 품은 도노히라 주지 승려는 지역 주민들과 함께 '소라치 민중사 강좌'라는 시민단체를

조직하고 강제징용 희생자에 대해 조사하는 활동을 펼쳤다. 이들은 위패에서 증언하고 있는 내용을 토대로 한국의

유족에게 연락해 희생자의 유골을 고향으로 돌려보냈다. 이러한 희생자 유골 발굴 활동은 1997년 한일 공동 워크숍을

계기로 두 나라의 시민들과 학생들이 더 많이 참여하면서 규모가 커졌다. 무엇보다도 한일 시민 사회가 함께 역사의

사실 앞에서 서로를 이해할 수 있는 '교류의 장'을 형성한 것이 의미있었다.

〈70년 만의 귀향〉은 홋카이도에서 그간 발굴된 유골 115위를 수습하고, 징용자들이 끌려간 그때의 길로 되돌아오는

귀향단 여정을 기록했다. 이 여정은 송기찬 교수가 기획했다. 한국에서 출발하고 돌아오는 약 3,800킬로미터 열흘간의

여정은 때마침 2015년 광복 70주년이 되는 해였다. 세관, 검사, 통관 등 여러 문제들이 발생하는 비행기 대신 버스와

배를 통한 여정으로 구체화했다.

2015년 9월 11일 하마톤베쓰에 도착한 귀향단은 이튿날 홋카이도 북쪽에 위치한 아사지노 텐유지 절을 방문했다. 이곳은

일본 육군 비행장 강제 노동 희생자 34위 유골을 임시로 안치하고 있었다. 그 날은 추모식이 열렸다. 추모식을 마치고

슈마리나이 사사노보노효 전시관을 들러 유골 4위를 운구했다. 이후 미쓰비시 비바이 탄광에서 희생된 6위의 유골과

정토진종 삿포로 별원에서 합골한 한국인 희생자 유골 71위를 모시고 삿포로를 떠났다. 삿포로 시에서 1시간 정도의

남쪽에 위치한 토마코마이 항구에서 배를 타고 이바라키현의 오아라이 항구로 향했다. 두 번의 바다를 건너며 절망했던

징용자들의 바닷길이었다. 도쿄에 도착한 귀향단은 도쿄 쓰키지혼가지에서 열린 추모식에 참석하여 임시로 안치한

유골함을 모시고 교토로 떠났다. 교토, 오사카, 히로시마, 시모노세키를 차례로 들러 희생자를 추모하고 유골 115위가

고국으로 돌아가고 있다는 것을 일본 사회에 알렸다.

귀향단은 시모노세키에서 대한해협을 무사히 건너 부산항에 도착했고 노제를 올린 후 장례식이 거행될 서울 시청

광장으로 이동했다. 많은 자원봉사자와 유족들 시민들이 참여했다. 장례식을 치른 뒤 유골은 화장을 거쳐

서울시립추모공원(파주 용미리)에 안장되었다. 이와 같은 시민 사회의 노력에도 불구하고 아직도 바다 건너 고국으로

돌아오지 못한 희생자가 많다. 일본이 확인한 강제 징용자 희생자 유골만 2643위. 이마저도 지자체와 불교교단에서

제공한 정보만 합한 것이다. 2019년 한국 법원의 일제 강제 징용 판결로 일본 정부는 강제징용 마저 외면하며 한일

관계는 악화일로를 걷고 있다. 두 나라의 냉랭한 분위기에도 불구하고 한일 시민사회는 강제동원 희생자 유골봉환

문제에 연대하고 지속적으로 협력하고 있다. 2019년 2월 28일 강제징용 희생자 유골 74위가 80년만에 고국으로 돌아온

것도 양국 활동가들과 종교인의 노력이 크다.

안타깝지만 시간은 우리 편이 아니다. 2020년 11월 '강제징용 역사의 산증인' 재일 동포 강경남 할머니가 향년 95세로

별세했다. 8세 때 징용된 아버지를 따라 일본으로 온 강경남 할머니는 강제 징역 1세대 중 마지막 생존자였다. 시간은

얼마 남지 않았다. 유족과 생존자가 기억하는 희생자 이름이 어두운 심연으로 침전하기 전에 유골을 찾고 가족의 품으로

돌려보내야 한다. 한 줌의 유해는 한때 인간이었고 가족이 있었고 우리였다.

징용자 아리랑

정태춘 작사,작곡, ‘달아 높이곰’

달아, 높이나 올라 이역의 산하 제국을 비추올 때 식민 징용의 청춘 굶주려 노동에 뼈 녹아 잠 못 들고 아리 아리랑,

고향의 부모 나 돌아오기만 기다려 달아 높이나 올라 오늘 죽어 나간 영혼들을 세라

달아, 높이나 올라 삭풍에 떠는 내 밤을 비추올 때 무덤도 없이 버려진 넋들 제국의 하늘 떠도는데 아리 아리랑, 두고

온 새 각시 병든 몸 통곡도 못 듣고 달아, 높이나 올라 내 넋이라도 고향 마당에 뿌려라

아리 아리랑, 버려진 넋들 고향에 돌아가지 못하고 달아, 훤히나 비춰 슬픈 영혼들 이름이나 찾자 고향엘 들러야 저승길

간단다 달아, 높이곰 올라라 달아, 놈이곰 올라라

비평글

기억할 것인가,

망각할 것인가

박평종(미학, 사진비평)

전시 〈70년 만의 귀향: 돌아오지 못한 영혼들, 돌아오지 못한 사람들〉에서 손승현은 일제강점기의 한국인 강제징용

문제를 다루고 있다. 전시는 크게 네 부분으로 나뉜다. 1부는 2015년에 이루어진 북해도 강제징용 희생자들의 유골 귀환

여정에 대한 다큐멘터리 작업이다. 2부는 희생자 유골 반환과 관련된 각종 현안을 다룬 2011년부터의 작업, 특히

슈마리나이 호수 댐 건설에 강제 동원됐던 노동자들의 문제를 다룬다. 3부는 강제 징용자를 비롯하여 희생자 가족,

원폭피해자, 사할린 강제 징용자들의 초상을 중심으로 그들 삶을 회고하는 당사자들의 목소리를 함께 들려준다. 4부는

슈마리나이의 사찰 광현사를 개보수하여 설립한 사사노보효 전시관의 강제징용 관련 아카이브 작업이다.

1부 〈70년 만의 귀향〉은 북해도 지역 한국인 강제징용 희생자의 유골이 2015년 한국으로 귀환되는 과정을 집중적으로

보여준다. 1997년부터 한국과 일본의 시민단체 주도로 이루어진 발굴 작업을 통해 총 115인의 희생자가 죽어서나마

모국으로 돌아올 수 있었다. 북해도에 강제 징용됐던 한국인 노동자의 정확한 통계수치는 불확실하나 희생자가 수천에

이를 것이라 추정하고 있다. 또한 생존자들의 증언과 후일 연구조사를 통해 입증된 사실관계에 비추어 보면 강제노역의

강도나 처우, 열악한 노동환경 등을 고려할 때 이 강제징용이 대단히 잔혹한 ‘반인륜적 범죄’였음을 알 수 있다. 그러나

강제징용 배상 문제와 관련하여 일본 정부가 취하고 있는 입장을 보면 이 문제는 여전히 진행형이다. 예컨대 2018년

강제징용 피해자들이 신일철주금(일본제철)을 상대로 낸 손해배상 청구소송에 대한 한국 대법원의 판결과 관련하여

일본정부는 잘못을 인정하지 않는 태도로 일관하고 있다. 말하자면 일본정부는 이 강제징용에 대한 보상은 이미

끝났으며, 결국 진정으로 사죄해야 할 범죄로 보고 있지 않다. 1부 작업은 북해도의 아이누 부족도 함께 다루고 있다.

아이누 부족은 본래 북해도에 거주하던 원주민으로 메이지 유신 이후 일본 정부의 탄압으로 현재 소수민족으로 전락한

상태다. 강제징용으로 북해도에 끌려갔던 한국인 노동자들 중에는 가혹한 강제노동을 견디다 못해 탈출하여 아이누 부족

공동체로 피신한 경우가 많았는데, 그 후손들에 관한 내용도 여기에 포함되어 있다.

2부 〈돌아오지 못한 영혼들〉은 북해도 슈마리나이 댐 건설에 징용됐던 희생자 관련 작업이다. 슈마리나이 댐은 일본이

1938년부터 1943년 사이 군수물자 보급에 필요한 전력 확보를 위해 건설한 수력발전소다. 이 댐의 건설에 동원됐던

노동자 중 200여명이 혹한의 추위와 가혹한 강제노동으로 사망했으며, 희생자 발굴조사를 통해 조선인 38명이 집단

매장된 사실이 밝혀진 바 있다. 이와 관련한 추모제와 문제 해결을 위한 다양한 행사 및 워크숍, 댐의 현재 모습 등을

담은 사진으로 구성되어 있다.

3부 〈돌아오지 못한 사람들〉은 강제징용자와 그들 가족의 초상, 회고담으로 구성된다. 작가는 1990년대부터 줄곧

비전향장기수를 비롯하여 아메리카 원주민, 코메리칸 등의 초상작업을 진행해 왔다. 이후에도 한국 근대현사의 굴곡

속에서 부득이하게 조국을 떠나 살 수밖에 없었던 재외 동포들의 초상작업을 계속하여 〈삶의 역사〉로 발표한 바 있다.

3부가 보여주는 초상들은 그 연장선상에 있다. 한 장의 초상은 ‘단지’ 인물의 얼굴만을 보여주지만 실상 거기에는 그

인물의 개인사가 깊이 각인돼 있다. 그리고 그 개인사는 내밀한 가족사, 나아가 한국 근현대사를 관통하는 거대한

‘민족사’와 겹친다. 강제징용은 해당 개인의 고통과 인권 문제를 건드리지만 가족사와 연계되어 시공간적으로 확장될

수밖에 없다. 그 사연들이 모이면 결국 민족사가 된다. 개인의 문제로 축소될 수 없는 것이다.

4부는 슈마리나이의 사찰 광현사를 개보수하여 건립한 사사노보효 전시관의 강제징용 희생자 관련 아카이브를 중심으로

구성된다. 여기에는 댐 건설과정에서 희생된 강제징용 노동자들의 위패와 각종 증명서 및 신분증, 관련 자료사진 등을

비롯하여, 이 전시관에서 정기적으로 진행되는 평화워크숍 관련 자료사진도 포함되어 있다.

전시는 총 4부로 구성되어 있지만 이는 형식상의 구분일 뿐이며 주제는 하나로 모인다. 작가는 이를 한마디로

“강제연행, 강제노동”이라고 언급한다. 실상 일제가 시행했던 징용은 정확히 ‘강제연행’과 ‘강제노동’의 형태를 띠고

있었다. 징용은 국가가 비상사태를 맞아 정상적으로 인력을 충원할 수 없을 때 행정 권력을 동원하여 시행하는

‘노동착취’의 한 형태다. 〈70년 만의 귀향〉 전은 1938년 공포된 ‘국가총동원법’에 의거하여 일제가 자행한 이

‘착취’의 희생자들을 다루고 있다. 징용은 때로는 행정 권력을 동원하여, 때로는 ‘자발적 지원’을 가장하여

무차별적으로 이루어졌음이 여러 증언과 조사를 통해 밝혀지고 있다.

징용이 전시와 같은 비상사태에 ‘합법적으로’ 허용될 수 있다는 사고는 어떻게 나온 것일까? 나치의 통치 철학에 일정한

자양분을 제공했던 독일의 정치철학자 칼 슈미트는 소위 ‘예외상태’에서는 개인의 인권을 희생하는 것을 감수해야

한다는 논리를 제공한 바 있다. 예외상태, 말하자면 천재지변이나 전쟁처럼 국가의 존립을 위태롭게 하는 상황에서는

법질서의 정상적 운용을 통해 위기를 돌파할 수 없다는 것이다. 이 경우 행정 권력은 일시적으로 법에 우선할 수 있다.

초법적 질서가 들어서는 셈이다. 물론 이 초법적 권력이 정당한가에 대한 판단은 다른 차원의 문제다. 또한 법을 가장한

초법적 권력이 ‘예외상태’를 상시적 질서로 구조화시키고 있음을 지적하는 아감벤의 통찰도 고려해야 한다. 어쨌든

일제강점기에 조선을 비롯하여 동아시아 전역에서 일제가 자행한 강제징용은 이 전체주의적 발상을 극단화시킨 형태다.

비상사태에서의 징용이 자국민에게는 허용될 수 있다 할지라도 타 국민에게 적용될 수는 없다. 따라서 일본의 이익을

위해 조선에서 자행된 징용은 명백한 범법행위였다. 일본이 1938년에 공포한 ‘국가총동원법’은 이 범죄를 합법화하기

위한 책략이었으며, 이를 근거로 관 주도의 주도면밀한 인력 모집이 이루어졌다. 그것만으로도 부족하여 1944년에는

‘국민징용령’을 공포하여 더욱 광범위한 강제징용이 시행됐다. 이는 모두 ‘법’을 근거로, 말하자면 ‘합법적으로’ 실시한

것이지만 결국 ‘합법’을 가장한 행정 권력의 남용일 따름이다. 나아가 징용희생자들의 증언과 관련 자료에 따르면 노동

당사자와 고용 주체 간에 체결한 계약 내용도 거의 지켜지지 않았음이 드러나고 있다.

이제 역사는 지나가고 희생자만 남았다. 심지어 〈70년 만의 귀향〉의 희생자들 대부분은 오랜 세월 동안 존재마저

망각되었던 이들이다. 제국주의 패권다툼과 2차 세계대전이라는 세계사적 흐름에서 누구도 자유로울 수 없기에 결과를

묵묵히 받아들이고 감내해야만 할까? 국가 주도로 자행된 ‘광범위한’ 폭력으로부터 개인이 비켜갈 수는 없다. 그런

점에서 징용의 희생자들은 거대한 폭력 앞에 속수무책 당할 수밖에 없었던 무력한 개인들, 말하자면 일종의 ‘호모

사케르’(아감벤)이기도 하다. 자신의 희생에 대해 항변할 대상조차 없었으므로.

그러나 그들의 희생을 잊지 않고 있던 이들의 오랜 노력 끝에 늦었지만 유골이 수습되어 고국으로 돌아오게 되었다.

유감스럽게도 이 각고의 노력은 국가가 아닌 한국과 일본의 시민단체 주도로 이루어졌다. 어떤 국가는 무자비한 폭력을

저질렀고, 또 다른 국가는 그 폭력의 희생자들을 보호하지 못했다. 또한 폭력의 주체였던 국가는 희생자들에 대한

참회나 보상에 진정성 있는 태도를 한 번도 보여주지 않았고, 희생자들을 껴안아야 했던 국가는 그들을 망각의 수렁에서

건져 올리려는 적극적인 시도를 하지 않았다. 또한 강제징용이 국가 주도로 이루어졌다고 해서 노동을 수탈한 기업에

책임이 없지는 않다. 현재까지 밝혀진 수많은 사례들에서 보듯이 소위 ‘전범기업’들은 징용으로 끌어 모은 값싼 노동을

통해 천문학적 이윤을 남길 수 있었다. 그 과정에서 벌어진 각종 범법행위도 부지기수다. 말하자면 ‘반인륜적 범죄’는

민관 합작으로 은밀하게 자행되었다. 이 총체적 범죄행위를 밝히고 희생자들의 넋을 위로하고, 정당한 보상의 절차를

밟는 등 뒤틀린 역사를 바로잡는 모든 노력은 피해 당사자 개인의 몫이었다. 물론 정치, 외교적으로 복잡하게 얽혀있는

실타래를 풀기는 쉽지 않다. 우선 당장 일본 정부의 완강한 태도가 문제지만 과거를 덮을 수는 없다. 시간이 걸리더라도

지속적으로 사실관계를 파헤치고 문제를 제기하여 역사적 진실을 온전히 밝혀내야 한다.

손승현의 작업이 갖는 의미도 여기에 있다. 징용희생자 유골 115구를 발굴하여 국내로 송환하는 데 70년이 걸렸다.

수많은 희생자들 중 극히 일부일 뿐임에도 그만큼의 세월이 필요했다면 아직 채 밝혀내지 못한 또 다른 진실에 접근하는

데는 얼마나 오랜 시간이 걸릴지 알 수 없다. 광현사 아카이브가 보여주고 있듯 제 아무리 ‘사소한’ 기록도 후일 역사적

사실을 입증하는 데, 그리고 그 사실을 집단의 기억으로 보존하는 데 귀중한 자료가 된다. 개인의 기억과 객관적 기록이

함께 할 때 그 효과는 증폭된다. 작가는 3부에서 희생자의 증언(기억)과 4부에서 아카이브(기록)를 적극 활용하여

과거를 소환한다. 그것만으로 충분하지 않다. 역사를 대하는 오늘의 자세를 기록으로 남겨놓는 것도 필요하다. 기록

없이 역사는 망각되기에.

작가는 강제징용 관련 작업을 진행하면서 나치의 홀로코스트를 떠올렸다고 밝힌 바 있다. 맞는 말이다. 두 사태의

양태는 달라도 본질은 같다. 나아가 이 ‘반인륜적 범죄’는 동아시아 근현대사에서 갑자기 출현한 ‘특수한’ 사태가

아니다. 인간이 인간에게 행한 그와 유사한 집단적 폭력과 잔혹한 범죄는 문명사 전체를 관통해 왔다. 물론 반성도

있었고, 참회도 있었다. 그러나 과거는 쉽게 망각되고 폭력의 역사는 계속 반복되어 왔다. 작가의 언급처럼 일제의

강제징용과 나치의 홀로코스트는 같은 본질을 갖고 있지만 ‘범죄’에 대한 참회의 방식은 다르다. 수없이 지적되어 온

바이지만 홀로코스트에 대한 독일 정부의 진정성 있는 반성과 전범자에 대한 단죄의 방식은 일본 정부의 미온적 태도에

비할 바가 아니다. 진정한 뉘우침이 없다면 유사 범죄는 언제라도 다시 발생할 수 있음을 문명사가 입증하고 있다.

이런 맥락에서 손승현의 사진 기록이 할 수 있는 일은 현실을 지켜보고 보존하여 미래에 물려주는 것이다. 과거에 어떤

반인륜적 범죄가 자행되어 왔는지, 무고한 이들이 어떻게 희생되었는지, 그들을 추모하고 재발을 막기 위한 현재의

노력이 어떻게 진행되고 있는지, 이 모든 것을 낱낱이 기록하여 집단의 기억으로 보존해야 한다. 반인륜적 범죄는

문명이 지속되는 한 결코 망각되어서는 안 되기 때문이다.

돌아오지 못한 사람들

〈돌아오지 못한 사람들〉은 재일 동포들의 삶 이야기이다. 동시에 일제강점기와 한반도 분단으로 인해 고국으로

돌아오지 못한 재일 동포들의 얼굴을 포착하여 한국 근대사의 그림자를 전시한다.

일본은 전쟁 체제에서 인력 확보를 위해 1938년 국가총동원법을 공포하고 조선인들을 강제로 연행했다. 이에 동참한

몇몇 일본 기업들은 매우 열악한 환경에서 강제 노역을 시켰고, 그 과정에서 수많은 사람들이 목숨을 잃었다.

1938년부터 1945년까지 일본 본토로 강제 징용된 조선인만 100만 명으로 추정하며, 한반도 내에서 전쟁을 위해 동원된

징용자는 450만 명에 이른다. 모두 합하면 550만 명을 강제동원 했지만, 실제는 이보다 많은 800만여 명에 달하는

것으로 추산한다. 이 전시에서는 일본으로 강제로 끌려간 재일 동포들의 과거 이야기와 거주권과 생존권 문제와 같은

현재 이야기를 다룬다.

“돌아오지 못한 사람들” 이야기는 시민들의 참여가 발단이 됐다. 1980년대, 일본 시민과 종교인은 훗카이도 강제노동

희생자 유골을 발굴했다. 이후 1997년부터 2014년까지 17년간 한국과 일본의 민간 전문가들, 학생과 청년들이 함께

유골을 추가로 수습했다. 이들이 수습한 유골은 태평양 전쟁 당시 홋카이도 지역으로 강제 징용된 희생자 유골 50여

구와, 인근 사찰에서 100여 구 등 총 150여 구에 달했다. 이 지역에 강제 노동으로 희생된 한국 사람들의 유골은 이들이

찾아내기 전까지, 50년 이상 잊힌 채 방치된 사람들이었다. 양국 정부의 대화가 멈춰있는 동안 한일 시민사회는 직접

나서 발굴하기 시작했다. 이처럼 전시 〈돌아오지 못한 사람들〉은 국가 간 갈등을 넘어 양국 시민들이 서로 이해하고

공감하는 모습을 담아낸다. 또한 지속적인 교류로 이뤄지고 있는 유골 발굴과 같은 활동을 기록한 사진도 살펴볼 수

있다. 아직도 돌아오지 못한 사람들이 있는 지금, 이들의 이야기는 근대사와 현대사 사이에 유령처럼 떠돌고 있다.

비평글

카메라는 노인들의 눈에서

빛을 도로 찾아줄 수 있을까?

이영준

노래가 소리를 잃는다면 얼마나 슬플까? 슬프기에 앞서서, 우리는 노래의 호소를 들을 수 없을 것이다. 노래의 소리는

악기와 결과 분위기와 양식에 따라 다성적(polyphony)이므로 그 호소도 매우 다층적이다. 만일 한 가지 방식으로

호소해서 통하지 않으면 다른 방식을 쓰면 된다. 피리로 호소했는데 안 통하면 북으로 호소하면 된다. 따라서 소리의

호소를 한꺼번에 잃는 일은 일어나지 않을 것이다.

사진이 빛을 잃는다면 얼마나 슬플까? 오늘날 빛의 가치가 하락함에 따라 빛의 예술인 사진도 그 가치를 잃고 말았다.

빛이 귀하던 시절에는 작은...

[ Read more + ]

기억이 살아있으면

그 사람은 살아있다

손승현

상처, 너는 모든 길을 만들지 세상에 없는 길을 만들기도 하지

조팝나무가 남기고 산 꽃길처럼 저 깊고 환한

상처 / 윤홍조

냉전체제의 붕괴 이후 국가 간 자본과 노동력의 이동이 그 어느 때보다 활발하다. 짧은 시간 비약적 경제 성장을 이룩한

한국 사회 또한 IMF 위기 이후 신자유주의 시장이 가속화 되면서 물리적인 국가 경계를 포함한 사회, 정치, 경제, 종교,

문화의 경계가 약화하기 시작했다. 신자유주의는 한국 사회를 빠르게 변화시켰다. 노동 환경의 변화로 이주 노동자,

결혼 이주민이 한국 사회에 편입되고, 이를 계기로 이주에 관한 시선은 수많은 코리안 디아스포라들에게까지

확장됐다.

코리안 디아스포라는 정치, 경제, 종교, 역사적인 이유로 이주를 경험한 사람들이다. 이들 상당수는 불행했던 한국

근대사로 인해 사할린과 중국, 중앙 아시아, 미주 지역 등으로 이주/이산 했던 사람들이었다. 거주국 사회에서

유색소수민족으로 차별받기도 한 이들은, 타민족의 문화를 수용하면서도 민족 정체성을 지키고자 했다. 현재 이들의

터전은 해외에 있거나 긴 노마드 시간을 청산하고 한국 땅에 정착해 살고 있다. 그러나 한국으로 돌아온 이들에게 향한

건 차가운 시선이었다. 또한 처음부터 한국에 거주했지만 사회로부터 배제되었다고 말하는 사람들도 있다. 이들은

한국전쟁 전후, 좌익세력으로 분류되어 처벌 받고 오랜 시간이 지나서도 낙인 찍힌 가족과 후손들까지 차별과 냉대 속에

어려운 삶을 살고 있다.

이곳에서는 러시아 사할린 교포, 중앙 아시아 고려인 동포, 조선족 동포, 북한 이탈 주민(새터민), 재일 동포, 재미

동포들을 비롯한 코리안 디아스포라, 낙인 찍힌 한국 사회의 소수자를 만나 기록했다. 이들은 개인의 가족사와 고단한

타국 삶의 애환을 말한다. 또한 주류 역사 속에서 감춰지고 소외되었던 자신들의 정체성은 어떤 것인가 하는 이야기도

담았다. 이들이 증언하는 이야기를 통해 타인에게 배타적인 한국 사회가 우리 모두가 함께 사는 다문화 사회로 나아가길

바란다.

사사노보효(笹の墓標)

강제노동자료관

아시아-태평양 전쟁 중 이곳 슈마리나이(朱鞠內)의 우류(雨竜)댐과 신메이센(深名線)철도 공사에는 수많은 조선인과

일본인 타코베야 노동자들이 혹독한 강제노역에 동원되어 200명 이상 희생되었다. 사망자 중 이름과 본적지로 확인된

조선인은 48명에 달한다. 그 희생자들은 가족들조차 생사를 알지 못하는 가운데 이역 땅 조릿대(사사) 수풀 밑에 묻혀서

잊혀 갔다.

1976년 이곳 코켄지(光顯寺)에서 위패가 발견되어 소라치(空知)민중사강좌의 시민활동가들이 유해 조사와 발굴을

시작하였다.

1997년부터는 한국, 일본, 아이누, 재일 동포와 여러 나라의 청년 시민들이 참여하여 ‘과거를 마음에 새기고, 현재의

서로를 이해하고, 미래를 함께 열어가는’ 동아시아 공동워크숍을 매년 개최하였다. 이들이 함께 발굴한 유골은 2015년

추석, 고국으로 돌아가 서울시립묘지(파주)의 ‘70년 만의 귀향’ 묘역에 안장되었다.

일본에서 가장 추운 슈마리나이에서 희생된 강제노동 희생자들을 기억하고 추모하기 위하여 그들을 임시 안치했던

이곳에 ‘사사노보효(笹の墓標: 조릿대 묘표) 강제노동자료관’을 조성하여 화해와 평화의 출발점으로 삼고자 한다.

(한국) 평화디딤돌 – (일본) 동아시아시민네트워크

감사의 말

전시 ⟨70년 만의 귀향⟩은 2011년부터 2018년까지 7년 간 한국과 일본의 여러 도시를 다니며 촬영한 사진으로

구성했습니다. 이번 전시를 위해 많은 분들이 도움과 조언을 주셨습니다.

제 부모님 고 손문성님과 이길례님, 형제 승환과 수미, 미정. 제 선생님 김우룡님과 Martha Rosler. 아내 김윤선과 딸

손지안에게 감사합니다.

전시를 개최하고자 애써주신 이정은 선생님과 전시를 지원한 일제 강제동원 피해자 지원재단 관계자분들께

감사드립니다.

사사노보효(조릿대묘표) 아카이브 전시를 편집, 감수해 주신 박진숙님과 양월운님. 일어와 영어 번역을 진행해주신

김영환님, 최춘호님, 김아람님, 도노히라 유코님. 긴 세월 유골발굴과 한일 시민들의 관계를 연결해주신 도노히라

요시히코 스님과 정병호 교수님.

도움과 자문을 주신 김현태님과 송기찬 박사님, 박수진 박사님, 비평글을 써주신 박평종 박사님과 이영준 박사님,

온라인 전시를 구축하고 개발해주신 Rebel9 김선혁 대표님과 김정욱 실장님, 필름스켄과 디지털 이미지 리터칭을

담당해준 칼라랩 임형주, 장명준 실장님, 포스터를 만들어 주신 김영철님께 감사드립니다. 포스터 ⟨70년 만의 귀향⟩

글은 고 신영복 선생님의 헌정 글씨입니다.

그리고 한국의 평화디딤돌과 일본의 동아시아 시민 네트워크 회원들, 그리고 아이누 선주민 선생님들께 깊은 감사를

전합니다.

김정희, 정명희, 김영현, 강호봉, 홍리나, 강수행님 가족, 도노히라 히데미, 오가와 류키치, 오가와 사나에, 김광민,

정진헌, 변미정, 이성화, 리화미, 가게모토 츠요시, 채홍철, 김경수, 이 로사샛별, 윤건차, 고현태, 강주원, 강현진,

김서경, 김성용, 김수행, 김운성, 김현수, 데이비드 윌리엄 플래스, 호시노 쓰토무, 후지타니 코신, 요시다 쿠니히코,

테사 모리스 스즈키, 사카하라 에이켄, 야마자키 타다시, 키쿠치 노보루, 요시이 켄이치, 박묘광, 박선주, 안신원,

아이작 데이비드 내펠, 안효진, 오승래, 윤상석, 윤은정, 윤정구, 윤정하, 한효주, 김지윤, 변산노을, 박정우, 안성혁,

도노히라 카나, 방소형, 이경란, 이기범, 고바야시 히사토모, 키카와 테쓰닌, 키카와 신에이, 나카이 신스케, 도노히라

마코토, 무라타 마사아키, 소가 타이치, 이학수, 김윤기, 정우창, 정유성, 정윤주, 정태춘, 이애주, 정희윤, 채승언,

최자헌, 콜린 니콜 쿡, 황미정, 사사 히로코, 오에 타카유키, 스기타 히데아키, 스기타 류코, 야쿠치 켄, 마시코

미도리, 야구치 코이치, 키타무라 메구미, 키무라 카요코, 고바야시 치요미, 미치마타 카오리

기술노트

(Technical Notes)

사진 작업을 진행할 때 촬영하는 피사체에 따라 적합한 사진기를 고르게 된다. 나에게 있어서는 현장에서 피사체와 직접

대면했을 때 본능적으로 촬영이 빨리 이루어지는 조작의 간편함이 가장 중요한 기준이다. 거리에서 촬영한 사진과

정교하게 밝은 빛으로 만드는 초상, 그리고 시간을 가지고 긴 시간 응시하며 촬영하는 풍경 사진들은 적합한 카메라가

필요하다. 하지만 때로는 하나의 카메라로 이 모든 것을 해결해야 되는 상황도 종종 일어난다. 이번 전시에는 지난

8년간 촬영된 사진들 오만여 장 중에서 사진들을 선별했다. 사진을 촬영하는 것만큼이나 촬영한 사진들을 되돌아

살펴보고 하나의 주제로 편집하는 과정은 의미를 강조해주고 어떤 의미를 전달할지가 분명해진다. 전시와 사진집을

만드는 과정은 낱장의 사진이 하나의 주제로 묶는 결과물이라고 할 수 있다. 개인적으로 전시 보다는 보다 많은 내용을

중첩되게 다룰 수 있는 사진집이나 온라인 매체를 보다 선호한다.

사진기를 선택할 때는 여정과 피사체에 따라서 카메라가 결정된다. 이번 작업에서 카메라를 정하는 기준은 조작이

간단한 것들, 순간을 잡을 수 있는 카메라가 우선이었다. 그리고 주변 도움이 있을 때 여분의 중형 필름 카메라나

조명을 사용해서 초상 사진을 촬영할 수 있었다. 스냅촬영은 Sony A7R, Zeiss Sonnar T*35mm을 사용하다가

2016년경부터는 Leica X를 사용했다. 라이카에서 가장 조작이 간단하고 35밀리 고정렌즈로 만들어진 이 카메라는

움직이는 피사체를 담기에 아주 좋았다. 특히 흑백사진에 잘 맞는 톤을 표현해 주었다. 초상사진은 대부분

핫셀블라드(Hasselblad 553ELX)를 사용했고 클로즈업 사진은 80mm Carl Zeiss planar와 120mm Carl Zeiss Makro

Planar를 사용했다. 환경과 초상이 함께 나오는 사진은 40mm Carl Zeiss Distagon Lens와 Carl Zeiss Distagon

T*50mm를 교차 사용했다. 때로 초상 촬영에 사용한 전기 플래시는 Profoto 7B와 여행에 가지고 다닌 Profoto Acute

B600 조명을 사용했는데 배터리로 충전하는 방식이다. 작고 광량은 아주 강해서 야외에서 깊은 심도로 촬영이 가능했다.

2015년 〈70년 만의 귀향〉 여정에는 촬영 여건이 매일 변해서 안정적인 기록을 위해서 플레시(Nikon SB900)를 달고

촬영했다. 편집때 크로핑 등을 염두에 두었기에 큰 로우파일(Raw File) 저장이 가능한 니콘 D810을 사용했다. 렌즈는

24-70mm 줌 렌즈 하나로 모든 일정의 촬영을 진행했다.

삼각대(Gitzo GT2542)는 예비로 가지고 다녔으나 많이 사용하지 않았다.

1990년대부터 사용했던 필름 카메라 Hasselblad와 Mamiya7, 43mm, 65mm, 80mm를 이번 전시작업에도 사용했다. 이

카메라들은 모두 초점을 수동으로 맞추는 방식이다. 필름 카메라를 아직 사용하는 가장 큰 이유는 뷰 파인더에 오랜

기간 적응된 내 눈 때문인데 촬영을 할 때 원하는 모습으로 편안하게 촬영을 진행할 수 있다.

중형 카메라에는 흑백, 컬러 필름을 모두 사용한다. 흑백필름은 코닥 트라이 엑스(Tri-x)필름을 사용했고 컬러필름은

코닥 포트라 Portra 160NC를 선호한다. 트라이 엑스 필름은 D-76 현상액을 물과 1:1로 희석해서 사용했다. 이 현상법은

긴 현상시간으로 인한 여러 단계의 흑백톤을 얻는 데 효과적이다. 컬러필름은 C-41현상을 한 뒤 밀착인화로 만든 후

사진을 골라낸다. 흑백필름은 현상 후 밀착인화를 한 후, 11×14인치 인화를 하는데 코닥 덱톨 현상액(KODAK Dektol)을

물과 1:2로 희석해서 사진을 인화한다. 인화지는 일포드 멀티그레이드 화이버 베이스 인화지(ILFORD Multigrade

fiberbase paper)를 사용했고 흑백인화는 베셀라45 (Beseler 45MXT)와 로덴스톡 로다곤(Rodenstock Rodagon) 80mm

렌즈를 이용하여 인화했다.

디지털 이미지는 사진이 선택되면 아도비 로우(Adobe Raw)와 아도비 포토샵(Adobe Photoshop)을 이용해서 디지털

리터칭을 진행했다. 이번 전시에 들어간 사진들은 필름 사진과 디지털 사진이 뒤섞여 있다. 필름 사진들은 이마콘

스캐너(Imacon flextight scanner)를 이용해서 필름 스캔 후 어도비 포토샵으로 처리했다.